On a bridge over the river Saalach I crossed into Austria. I stopped two elderly Austrian ladies in the middle of the bridge who were headed the opposite direction, and they very enthusiastically agreed to photograph the event. Having told them where I had started and where I was headed, they shook their heads in disbelief and began stopping other passersby, relaying the tale. In amused embarrassment, I continued to pose for the photo for one of the ladies holding my phone, while the other continued exclaiming “Constantinople” and gesturing at commuters who struggled to pass us on the narrow bridge, weaving their bikes between the three human obstacles crowding their way. The ladies took their commission very seriously, and I struggled not to laugh as they continued to adjust the angle of the shot and fuss over the lighting conditions. Eventually, the final results were secured. They asked me why was I doing my trip, and in the interest of brevity, I answered, “Why not!?”. This prompted a laugh from one of the ladies; the other wasn’t fully convinced, I don’t think. I headed for Austrian land.

Songs they have sung for a thousand years

It took me around an hour and a half to reach the centre of Salzburg: all of a sudden, I was in the middle of the old town. I walked through the cobbled streets of town and sat a while by the river Salzach. Soon, in the early evening, the city was enveloped in a deep orange haze, much to the confusion of Salzburgers and me. (I would later discover this was the work of a Saharan dust cloud sweeping over Western Europe). Then, the drizzle began and I found my way to Mirjam’s flat, my hostess for the next couple of nights.

After showering off the dust of the road, Mirjam and I sat down to eat the supper of calamari, potatoes and salad she had kindly prepared. Over a bottle of sweet white wine, we talked long into the evening about life in Salzburg, and her career as a social worker for teenagers: her love and genuine concern about the latter was touching. After a few hours, tired from the road and the momentous nature of the day, I went to bed on the sofa bed in the living-room-cum-bedroom of Mirjam’s flat.

I spent the next day tromping around the city of Salzburg, ambling down the riverside promenades and cobbled streets of Mozart’s hometown.

Into the hills

Bidding farewell to Mirjam early the next morning, I headed out of Salzburg into the hills and mountains of Austria. I walked largely along the sides of B roads or along cycles lanes: the “cycle lane strategy” was beginning to fall away at this point — options in Bavaria had gradually become scarce, and opportunities in Austria were less common still; I was slowly figuring out alternative sustainable walking strategies.

In the early evening, I stopped at an inn by the side of an A road I had been forced to follow for a couple of hours. The inn was part of a hamlet called Watzlberg which stretched for no more than 300 metres along the road, with the Alps off in the distance. As I ate supper that evening in the traditional Gasthof downstairs, I overheard a group of young Germans (their accent suggested Western Germany) in rowdy conversation in a booth across the room. Rather amusingly, every thirty seconds, whomever happened to be speaking would randomly insert an English word or phrase into their drunken spiel, before continuing in rapid German. This reached its climax when one young man began an impersonation of a Boris Johnson interview and his “BLU” passports (a viral meme from the past couple of years). Even in obscure hamlets hidden in the Austrian hills, nowhere was safe anymore.

Departing the next day following a hearty breakfast and a handshake from Franz Joseph Jr., the hotelier, a hard day of walking followed. I stuck largely to the side of a main road, walking briefly on the tarmac, before darting out the way of oncoming traffic, or else by walking on the dirt and dusty grass immediately next to the road: so went most of a tiring day. My hotel that night in Vöcklabruck was bizarrely furnished in period decor.

Succumbing to my river-walking withdrawal of the past few days, I soon found myself once more following a waterway: the Ager river, which soon became the river Traun as I arrived in Lambach. The river is a tributary of the Danube, which I expected to meet it near Linz, having followed the Traun northwards. With all this talk of rivers, I had an exciting thought: I was now on a river all the way to Budapest. It was a big moment; I was firmly back in the realm of the Danube.

Open doors

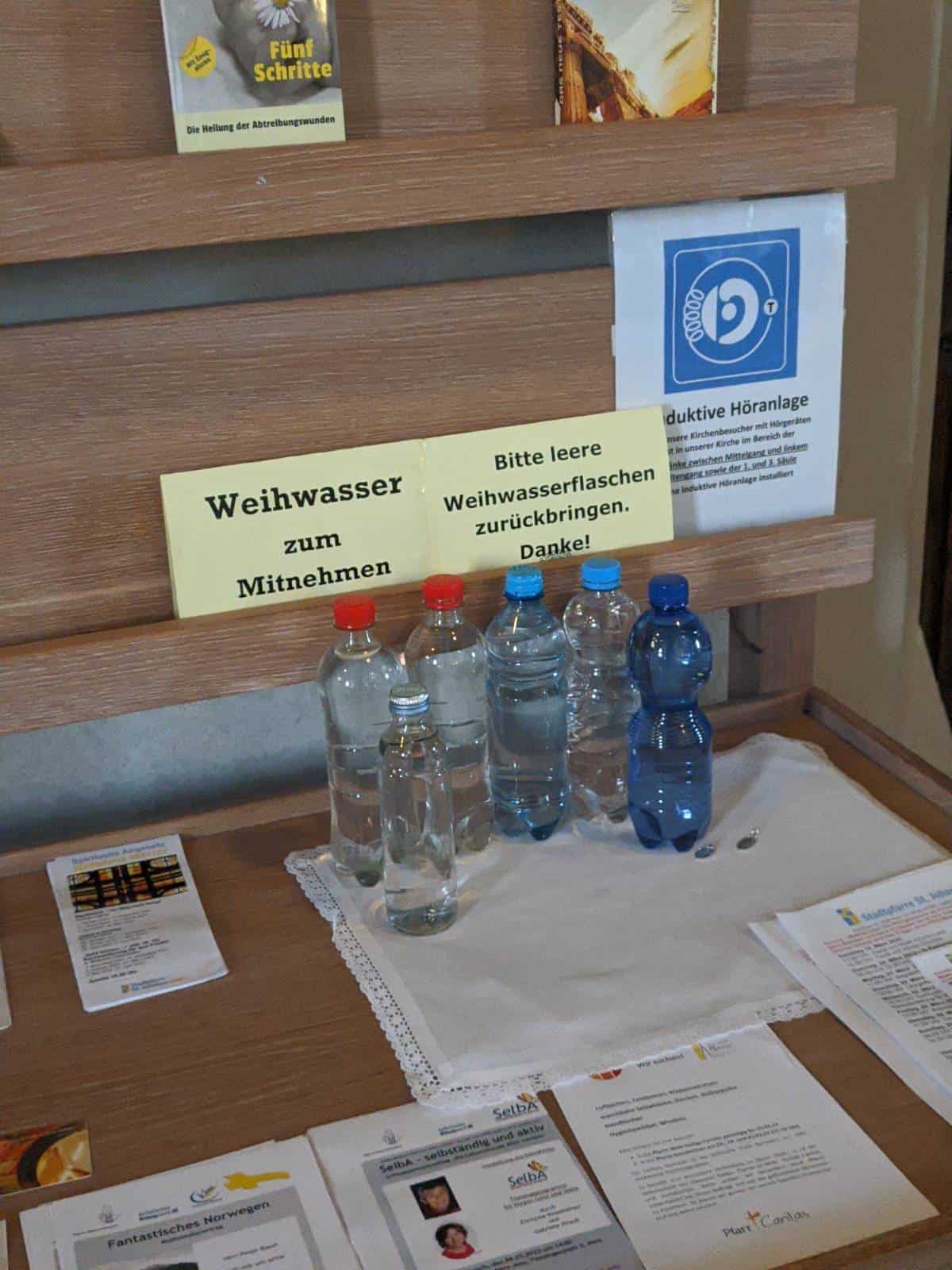

Having reached Lambach relatively early, I hid my stick around the back of a potential Gasthof for that evening and headed for the seed of the town: Lambach Abbey. It was a surreal experience; I had read online that the Abbey was closed to tourists until April, but as I entered the courtyard where there was a group of primary school kids on a class-trip running around outside the Abbey’s restaurant. Famed for its 19th century stone swastika-like decoration, which some say caught the eye of an infamous local schoolboy, I walked through the courtyard, and, on a whim, tried to open the door through into the monastery. It opened. Hesitant, I looked back at the courtyard behind me and went through the door. As I roamed around the working monastery’s quads (or should I say courts), every door I tried seemed to open. Even unlikely cast iron doors, likely not opened for decades, swung open, their hinges creaking. In this manner, I crept through the building, visiting various chapels, secluded courtyards and prayer rooms. It was wondrous. When I reached a block labeled “Konvent” I paused, not wanting to wear out my door-opening luck, and not wanting to disturb the monks within. As I circuitously retraced my steps, in the corner of the inner courtyard, I noticed a chapel door I had previously overlooked. Prying open the door, I was greeted by a baroque altar. Another door, almost half my height, hidden in the corner of this chapel, led into a dimly lit room. Once my eyes had adjusted, the medieval world surrounded me; old, fading frescos covered the walls, and flaking plaster revealed slim, Roman-style brinks still holding up the walls. I later learnt these frescos constituted the oldest surviving in all of Austria and the southern Germanic world.

In Wels the next day, I dropped my bag off in a room above a restaurant in the outskirts of town: a pretty run down place, but not quite decrepit. At least not quite yet. I headed off in search of the old town, about half an hour away. Passing through the Ledererturm, a tower which serves as the last remnant of Wels’ medieval fortifications, I arrived in the main square. The central street and square of the city were framed by slender town houses, many of which conceal arcaded inner courtyards. I soon arrived at the House of Salome Alt which sported a trompe l’oeil facade. (The mistress of the Archduke of Salzburg, Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau, once resided therein.) Those were the main attractions.

Running into some American tourists around my age, I somehow ended up in a shisha bar in the centre of town: clearly the place to be on evenings in Wels, though I doubt I qualified for entry on the hairstyle front, as I watched dozens of young men with skin fades enter. Not long later, I traipsed back across the outskirts to my bed.

I walked along the banks of the Traun for around seven hours the next day, during which my phone slipped from my pocket and shattered the screen on the ground. However, showing no signs of pathetic fallacy, the weather was glorious and settled into perfect walking conditions. Reaching Linz in the later afternoon, I headed first to the centre of the old town. The style of terracing in Linz, especially in the main square, resembled that of Wels, albeit on a larger scale; the scene comprised of painted façades, all faintly coloured, with ornamentation above the window panes, and piping in the stonework, the odd balcony, and a shallow covered arcade underneath. Eating a hunk of bread and some cheese, I drank it all in.

St Florian’s Abbey

It was a truly gorgeous day by the time my bus from Linz drew up in the town of St Florian the next day. The train line between the two, which carried Paddy in 1934, having been discontinued in the 70s, a half hour journey through the suburbs of Linz deposited me here, just a few miles south of Linz’s old town. (This was not without the inevitable initial teething problems of buying the wrong ticket and being reluctantly asked to wait for the next bus, before a mother with a stroller took pity on me and sorted out my fare troubles within a matter of moments. Too much walking — I had forgotten how to navigate public transport!) Climbing up the gravel hill path, my destination lay before me: the complex of St Florian’s Monastery.

The outer walls of the monastery were painted a faint sandy colour, and the strength of the sunlight ushered out the yellow hues. I passed through the archway of this great baroque masterpiece, into the primary courtyard, and into the ticket hall. The lady manning the desk broke the sorry news: “I’m so sorry,” she said, “The monastery isn’t open for tourists for another few weeks. Wenn man es bei diesem Wetter glauben kann, ist es immer noch unsere Winterpause!”. Despite the weather, it is still our winter break!

My despair plainly obvious, she reassured me that I could still wander around the outside of the buildings and explore the church. Not entirely placated, I leant into my “I’m a wandering pilgrim” look; genuinely sympathetic, she assured me that ordinarily she would have taken me around the site herself, but a couple of the monks had just contracted covid, and she was under strict instructions. The virus had struck again. I would have to make do; and make do, I did.

Ambling around the courtyards and cemetery gardens, I discovered that my monastic lucky touch seemed limited to Lambach. Following a staircase past a sign dictating Nur für Sängerknaben (choirboys only), I found myself in a side foyer filled with wooden confessional booths, all covered in dark oaken inlay and adorned with red velvet coverings. Beside them, a door was ajar. Through it, I entered the Abby’s church. Do indulge in some description…

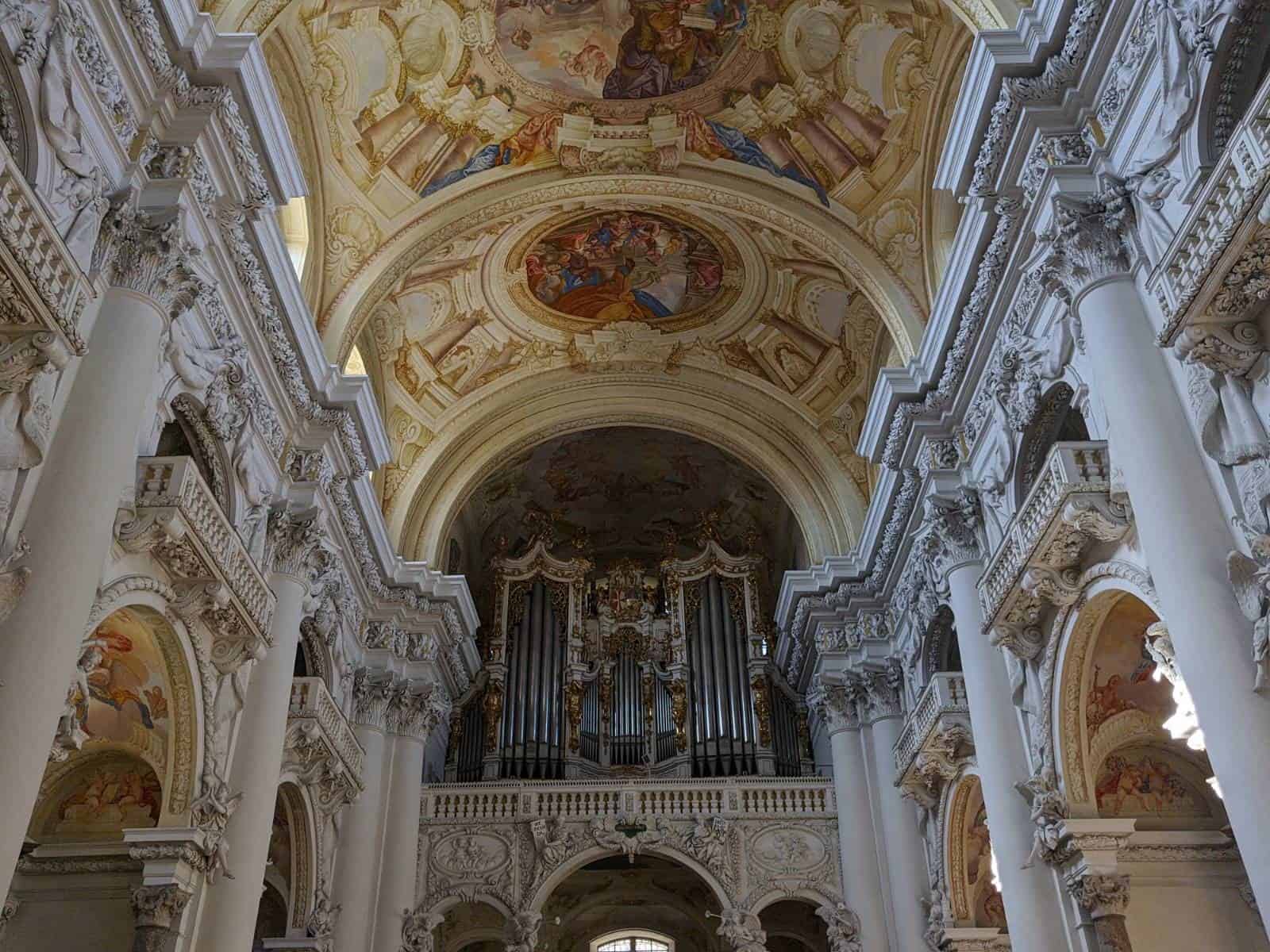

Miniature Solomonic columns carved from wood lined the sides of the pews in the nave — these columns were certainly a thematic constant of the church, consistent with the overwhelming Baroque style. The shallow domes of the ceilings were covered in rich Renaissance scenes, with angles and saintly figures all gesturing to the heavens. Two small organs faced one another above the quire, where a host of sculpted cherubims and putti flocked together. The little sculptures were all either playing golden bugles and violins, or gesturing down towards the congregation below. The scene in the rafters above was one of activity.

The midday light flooded in from the hemispherical port windows which lined the sides of the domes above. It glinted off the gold-leafed ornaments of the clerestory, and warmed the wooden furnishings below.

Spanning the wings of the nave were a row of thin marble columns, drawing the eyes towards the altar and ceiling. At the back of the church, twin white, corinthian columns rose to where the great organ lay above the narthex. The main organ – the Bruckner organ – somehow seemed slightly more reserved in its elegance, with its white and gold furnishings, than much of the rest of the church. Baroque is so easy to admire, but perhaps harder to love.

Back in Linz, I caught sight of my shaggy appearance in a shop window and decided it was time for a change. A haircut would mark my return to the Danube. I walked around town for the rest of the day. A noteworthy visit was to Linz’s New Church, the first Gothic monument for a long while: a Gothic holdout in a Baroque world.

Return to the Danube

I left Linz the following morning and, having picked up a coffee and pastry at Lidl, I wandered out of the city. I headed towards the bridge over the Danube, northeast of the centre of Linz. As I neared the bridge, a middle-aged man on a fold-up bike spotted me and dismounted alongside. He proceeded to asked me all about my trip and where I was headed, all very enthusiastic. “A spiritual journey! That’s amazing”, he remarked as he wheeled his bike abreast. When I mentioned I was heading to Mauthausen that day, his tone became suddenly somber: “That’s a sad place. Lots of pain.”. In the superficial way that only really comes about when speaking in a foreign language and limited by vocabulary, we both agreed that Hitler was a horrid, horrid man. He asked me what I was doing for food and, before I knew what was happening, he removed a crisp €20 note from his wallet and tried to hand it to me. “No, no, it’s okay don’t worry, thank you”. He wouldn’t hear it. He told me he hadn’t the time to go get lunch with me, but that I should look forward to a nice dinner at the end of the day and a cold beer: something to look forward to. After a little more persuading, I sheepishly accepted, taken with this random act of kindness. “Good luck!” he called back at me as he cycled away. Servus.

After crossing the Danube, I walked on a path along it for most of the day. I cut inland around 4pm and took a detour to the concentration camp to the northeast of the town of Mauthausen, just over the brow of a hill, with views out over the Danube and, in this fine weather, the peaks of the Alps to the south. I toured the camp and museum for most of two hours. In a much sobered mood, I set off down the hill towards the inn I had in mind. In a last-minute turn of events, that night ended with my having dinner with Werner, the second cousin of one of my close school friends. He lives in Enns, just across the river, which he had crossed to meet me in Mauthausen, and together we went to a restaurant a few hundred yards away from my inn. I had a creamy mushroom soup and then we both had a cordon bleu. The grub was excellent and over a couple of beers we discussed my trip and Werner’s travels of his own.

Back in Linz, I had sketched out my route down the Danube towards Vienna; making the most of the resources already at my disposal, I decided to stick roughly to Jakobsweg (The Way of St. James, or the path to Santiago de Compostela, on its Austrian leg), though, unusually, in reverse. The sand shell icons of the path marked the next few days.

I crossed the river into Wallsee the next afternoon. Spotting a Gasthof at the top of a hill I had ascended, I popped in and enquired about free beds. The woman enthusiastically said yes, and, having me pegged as a wandering pilgrim, beckoned me to sit in the courtyard. She returned with a large glass of beer. I sat there in the sunlight reading for a long while.

After spending a short while in the parish church across the way, I watched the purple sunset, sat outside the Gasthof, on the brow of the hill looking out across town, with the Schloss and the Danube’s hills as a backdrop. Returning inside, I found my way to a wooden bench in a restaurant area. Earlier, I had asked the hostess where would be good for a cheap supper. She had replied, “Why, we’ll make you something.”. And so, I went in blind: a beer was placed in front of me, and so too was a large bowl of carrot soup. That soon disappeared and a plate of cheeses and hams with slices of bread was put before me. By this point, word of my walk had spread through the family’s ranks and each generation took it in turn questioning me, as I sat dwarfed at my table intended for eight in the classically wooden Austrian interiors of the building. Eventually, I dragged myself upstairs to my bed above the stable block.

Vienna in the distance

I breakfasted the next morning at the same table at which I had supped. All the while, two pregnant dogs sat by my feet, their tails waging expectantly. After a long march across the countryside, cutting the corner off a section of the Danube, I arrived in Ybbs an der Donau in the late afternoon. I immediately headed across town to the Pfarrkirche St Lorenz where, as I had hoped, I happened upon the effigy of Hans the Knight, which had taken such a prominent hold in the minds of Paddy and his polymath friend 90 years prior to my arrival.

That night, waiting at a station quite in the middle of nowhere, a carriage drew up. And there, onto the platform, stepped a smiling, familiar face.

Aside: Greetings from Oradea. I arrived in Romania two nights ago and am about to make my way into the Carpathian mountains of Transylvania.

WHO IS THIS MYSTERY PERSON?!

highlight of the trip so far must have been that fresh trim

Undoubtedly so

Thanks Noah- congratulations & fascinating.

However have I missed sided something? It jumps from Austria & reaching the Danube with views towards Vienna to walking j in not Romania & Oradea?

Grandpops

Your Gt Gdad would have been interested in the Austrian section where he travelled, walked & climbed 90 years ago

Hiya. No, don’t worry! I’m gradually catching up, but just thought to mention where I am/was currently at the end, after the actual Austrian entry had finished 🙂

Still enjoying reading about your journey take care

Granny xxxx

Look in your bank xxxx

Thank you, Granny!!