Fear not, dear readers — I assure you that, as my hand has slowed down, my feet have sped up. This tale will have an ending.

We went south: through the freak downpours characteristic of mountainous regions, we sped along the newly completed motorway, skirting the western regions of Transylvania. Two hours later, we drew up by the site of the old Roman fort at Alba Iulia, a Transylvanian capital in days past. With the sun now back out in force, we strolled around the later-Hapsburg fortifications and restored old town. Then we drove to Sibiu.

An excursion to Sibiu

There were three main squares in town. We stopped for a beer in the first, and then wandered around the rest of the ensemble. Historically, Sibiu served as the capital of the Saxon settlement in Transylvania, and the town boasted a rather pretty blend of buildings. We remarked at length on the notable roof style which adorned many of the buildings lining the squares, where the dormers in between the clay tiles resembled slanted eyes peering across the town. Later, I discovered this to be an architectural feature greatly associated with Sibiu: dubbed The Eyes of Sibiu, and whilst centuries of myth-making have spread rumour of their supposed devilish and sinister origins, their true purport, as ventilation aids, is unsurprisingly rather more banal.

Hopping around town, sampling different beers, we looked out over the layers of the hilltop city. Then, when the squares took on the patina of night, we headed underground into an old Keller where a traditional Romanian-cum-Saxon feast of meats and breads awaited. It was only after the obligatory digestif in our favourite of the squares, Piața Mică, that we headed back for the night.

Our hotel that night, the Römischer Hotel (German for Roman), was quite the character itself: in decades past, it must have served as the swanky stay for Communist party members and guests, or for the hard currency of foreigners — it’s chandeliers, great red-rugged floors, and huge dining room, evoked the air of sophistication, but also verged on neglect. (I doubt it had seen any restoration since Ceaușescu’s fall.)

We raught at the mountains with outstretched hands

After a hotel breakfast taken in the expanse of the downstairs dining room, we departed Sibiu just after 9am.

Soon, snowy peaks emerged out of the clouds, hovering high up in the ether; we drove parallel to the Făgărăș Mountains for a short while, before turning south, veering straight for the foothills. Before long, we were winding our way up the beginnings of the famed Transfăgărășan Highway. The flora that surrounded us on our ascent became increasingly alpine. Due to the season, the upper reaches of the road were still closed due to the danger posed by the volatile and inclement weather, and we hopped out of the car some 1200m up the mountain. The remains of snowfall combined with icy dew as we trudged away from the car. Unfortunately, it soon transpired that the cable car we had wished to take to the lake at the top of the mountain, another 1000m higher up, had suffered a fault, so, after an hour of waiting, which included a short hike over to Bâlea waterfall, we called it a day. A Dutch family, which had earlier descended from the peak, painted a pretty picture up at top of easy winds and downy flake. And a frozen lake too.

Klausenburg

It was early evening by the time we arrived in Cluj, and, after checking in, we headed for the main square which lay in the shadow of St Michael’s Cathedral. Also situated in the Piața Unirii is a statue of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, a nationalist figure for both Hungarians and Romanians, and whose international and early European cooperation I had noted in my initial days in Hungary, when walking through the town of Visegrád.

After a few apéritifs of local porter beers and a late bite to eat, we wandered through fin-de-siècle alleyways, where club music and new-age bars exuded a young and partying aura.

The parallels of my Romanian road trip with that of Paddy’s were not lost on me; and although my trip was shorter – much shorter – and deposited me back where I had begun the drive; it seemed fitting this last-minute episode should have occurred when and where it did. My father’s arrival not only signalled a new and vehicular leg of the odyssey, but also heralded something much more practical and significant to my modus operandi: the arrival of my much-needed replacement boots. I had lived in my black Timberland boots for nigh on three months, over 1170 miles, and counting. They had really been so very brilliant and seen me through the countless adventures and through those early teething stages — but by now they were really rather a shadow of their former selves. The soles had worn thin, water had begun to seep into the leather, and their time was certainly long up (as I had first noted as I crossed the Great Plain).

My dad departed early the next morning and, after subdued goodbyes, I made my way across the old town to a hostel — under bittersweet circumstances, normal service resumed.

Cluj-Napoca, or, to the Saxons, Klausenburg, and to the Magyars, Kolozsvár, sits on the pre-Roman site of Napoca, once home to Dacian tribes. At the very heart of the historical and – though to a much lesser extent – modern day make up of Romania is its multiethnic composition — no more so than in Transylvania, where a mesh of Hungarians, Germans, Jews, Roma, Ukrainians, Bulgarians, and Romanians, all of varying creeds and religions, had come to congregate. Trade between the prospering states of Northern Europe and the Eastern Ottomans only further seasoned the ethnography. Cluj is also the birthplace of Ferenc Dávid the founder of the Unitarian creed, and thus a historical cauldron of religious development and, eventually, tolerance. And though Ferenc heralded from what is now not far from the very centre of the large land mass that constitutes Romania, he would have known his home as Kolozsvár of the Kingdom of Hungary. Names are fickle things in this part of the world, but the speakers of all the varied and transiting vernaculars left their marks on the land and rock — a rather more enduring legacy than the nomenclatures.

My hostel that evening lay beside the old city walls — in fact, the wall itself constituted the back paries of the building. I found myself wandering the town at night, talking aimlessly with students, before withdrawing into the shelter of my bulwarked abode.

Turda Gorge

After a blurry evening out in town, I was soon back following the dirt roads of the hilly countryside: up and down, and up and down. It was relatively hot, but the great wisps of cloud above obscured the sun for much of the day — not far from ideal walking conditions, these days.

Eight kilometres west of the town of Turda, I drew up at the mouth of a gorge, set into the foothills of the Apuseni. I wandered into and through the rocky chasm, an indisputable hidden gem of the journey.

Along the stream which cut through the rock, balanced trees sporting knotted trunks, which held aloft vines and colonies of ants; waterfalls lay in the shadows of looming massifs where, high above, the skeletons of shrubbery nestled into the cliff-side. Every inch idyllic, I traced along the bounds of the gorge, emulating the great explorers, both real and fictional; in emulation of Drake, Jones, and Cortes, I forded the river multiple times, crossing dubious rope bridges, reigning myself back from the precipice. At junctures, the watercourse grew to rapids tracking through the crenelated levels of boulders and pebble deposits. Showered in the rays of that golden hour of the afternoon, I emerged triumphant and giddy into a green pasture, just ahead of a group on a school trip.

Turda

Turda Gorge (Cheile Turzii) soon fell away behind me, and I arrived in the town of Turda. The centre of town was elegant in character. Like many I had come to in the past few days, the central old town – based firmly around the Piața Republicii – had clearly been recently restored, though not overly so: the character of the Secessionist buildings remained.

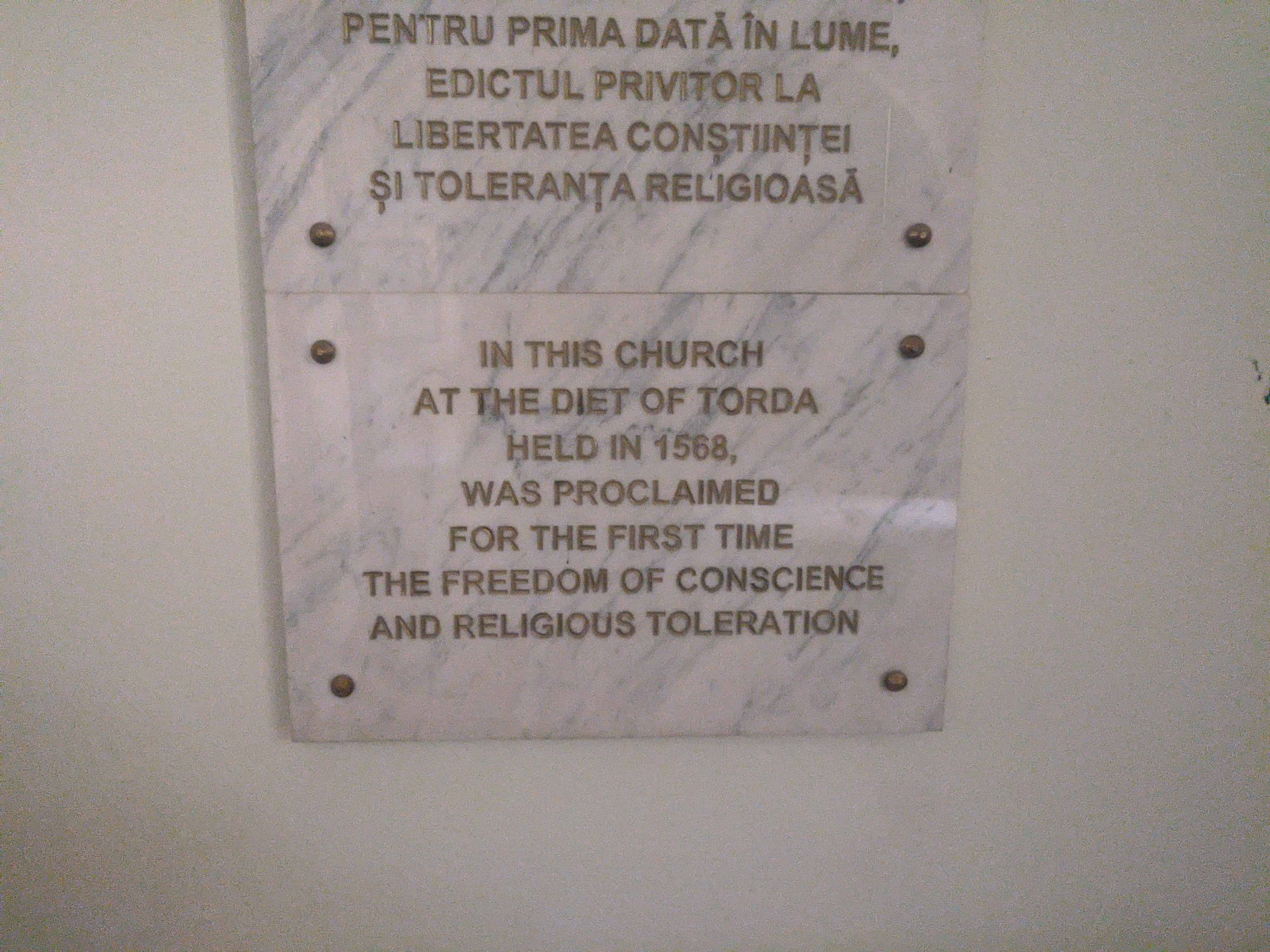

A plaque in the baroque Catholic church drew to my attention the significance of the town: the building was once the meeting place of the Transylvanian Diet and home of the 1568 Edict of Torda which recognised the equality of four faiths – Calvinism, Lutheranism, Roman Catholicism and Unitarianism – in Transylvania, attempting to preempt the spread of the period’s religious wars from further west. Notably, however, the Orthodoxy of the Wallachian people was omitted from the promulgation. Although it did not recognise an individual’s right to religious freedom, the edict represented a unique expression of religious tolerance: it acknowledged and permitted a radical Christian religion, Unitarianism, in Europe.

Anecdotally, the building itself appeared deceptive; a Gothic façade lay juxtaposed to the later Baroque remodelling undergone within. As night fell, I hung around the central avenue, observing as sleepy town cafés shifted into the subdued hum of new-age bars.

And on to Târgu Mureș…

I had stayed in a room a short walk away from the centre of the town, put up by a middle-aged husband and wife. A leisurely getting up followed the next morning with a lengthy discussion of the weather and terrain with my host, Basil, over a couple of cups of steaming coffee, the scent of freshly rolled tobacco wafting through the covered courtyard.

As I tromped through a field of wild flowers later that morning, I cursed my unhurried start as a long day of walking unfurled. A herd of goats ignored me from off the side of the fields, where they sat nonchalantly in the shade of a concrete ledge which emerged from a disused industrial estate, amusingly incongruous to the setting. A little further on, I passed a pen filled with grazing donkeys and, turning back for the first time that day, spotted the jagged shadow of Turda Gorge far behind. Again, I strode forward, browned calves disturbing the tawny tufts of dandelion heads, kicking silvery seeds into the sky.

A single, large NATO flag greeted me as I arrived in the apparently worldly and internationally conscious village of Iernut. The dark blue pennant had been hung beside the EU ensign, both flanked by countless red, yellow, and blue Romanian tricolours (a much more common facet of other such towns through which I had passed). Iernut, twinned with Geneva.

I ran around town trying to find somewhere to eat, as Penny Markt had closed, and it was a Sunday. A shawarma place on the other side of town had just shut, but near my apartment I managed to find a bar restaurant just before the kitchen closed. A young waitress helped me pick something off the Romanian menu. At first, we conversed in broken English, but then she realised I spoke German and we went steadily from there. I’d noticed that a surprising number of young Romanians either solely speak German as a second language or speak basic German and a smattering of broken English. That said, many do wield conversational English, though once you hit the demographic upward of 35 years old it becomes increasingly uncommon and I fall back to my well-practiced gesturing and shaky Romanian pleasantries! (Though, come to think of it, Basil, with whom I lodged the previous night, spoke near-fluent English and he was at least 60: not the first anomalous entity in my “rule of thumbs” this trip. It keeps things interesting, and me on my toes!)

I left Iernut early, over-compensating for my late departure the previous morning. In the mid-afternoon, I entered Târgu Mureș. I soon spotted two men dressed in white, surgical overalls, with English text that read “EU help us” ironed on to the front and back. My interest piqued, I realised they were stood in front of a long, roadside banner with block text reading: “We are faithful to Romania. We would like only to have a School of Medicine in our Hungarian native language.” The text was flanked with cartoon doves of peace proffering branches displaying Romanian and Hungarian colours in the beaks. Even with the death of any real irredentist threat to these regions, the assimilation of cultures and the standardisation of tongues poses a continued threat to the minorities: the all too real threat of European nationalist agendas. It is nothing new.

A change of tone

Between Cluj and here, I wasn’t all that far from the Ukrainian border — no more than 130 miles, by my reckoning. In many ways, I often find myself remarking and reflecting on the war in Ukraine and, perhaps just as significantly, the reactions – all supportive of a free Ukraine – of the peoples in the continent through which I walked. I have enduring memories of that dark and cold night in the outskirts of Heidelberg, sat by my new-found friend, Seb, watching CNN as Russian troops poured over the border. As the war raged on, and I continued east, solidarity with the Ukrainian plight remained vehement — light blue and yellow colours adorned the flagpoles of most towns, and it was not uncommon to find volunteers waiting outside stations ready to welcome fleeing refugees. Even now, tromping across rural and urban Transylvania, flags flew just as high as they had in February. As I passed by the station in Târgu Mureș, large, emboldened banners in both Latin and Cyrillic script proclaimed free transport across Romania for all Ukrainians. In all, a rare, solidary zeitgeist.

After a trip to the post office, I headed up to the fortress slightly above the main boulevard of town. Appearing recently restored, I ambled around the courtyard, past the church, and walked along the ramparts of the fortifications, which seemed to double as an elicit hiding spot for couples behind the nooks of the walls and mural chambers of the 17th century bastion and barracks.

Descending from the fortress, I entered the Orthodox Ascension Cathedral, which sits at pride of place at the end of the main street-cum-square, Theatre Plaza. (This practice of having a main street or boulevard which acts as the main square or centre of town was becoming increasingly common: Turda was the first place I noted this, and Târgu Mureș continued the trend. Even smaller towns, such as Iernut, followed a similar design). This was also the first place on my walk where Orthodoxy, or an Orthodox church, took centre stage. And it was breathtaking — a romanesque basilica styled on the Greek Cross, with the equally weighted arms of the Byzantine style. The interiors lay completely bejewelled in iconography and frescos. The blues, reds, yellows, and golds of the biblical scenes sprung from the ceilings, escaping through the gloom of the dimly lit space. A low-hanging, wide, brass chandelier hovered over the central aisle, and, opposite the entrance, taking centre stage, a white and gold iconostasis, ornamented and gilded, rose 15 metres up the back of the nave. It was rather gloomy inside, but there was also an odd yellow glow from the peripheries, owing to low down stained-glass windows in the side wings of the basilica.

Completing the necessary admin of the day at a café just off the boulevard, I wandered out to the north of town, where I found some cheap lodgings. It was only on my walk back that night, that I realised I was living near (and passing through) the Romani community. Some of the homes I peered discreetly into looked rather odd; in half-finished houses, I saw groups of traditionally dressed women old and young gathered around in sparsely furnished living rooms.

Sighișoara

Come the morning, I walked out from Târgu Mureș, continuing to Sângeorgiu de Pădure. Owing to the lack of suitable lodgings – this region was rather sparse – I, as planned, hopped on a train bound for the Saxon town of Sighișoara, intending to return to complete the leg the following day.

As the train rattled off down the tracks, I sat down by the window, not far from where a Romani woman perched with her son. She wore a brown and white cow-print skirt, which descended to golden frills by her ankles, and a white shirt with a faux-leather black waistcoat. Her black hair was half-covered by a purple and black shawl. Though she appeared older than she likely was, given her young son, I decided she was probably in her early forties. Her son sported well-worn, American-style sports apparel and two small rubber shoes.

After a short while, as I watched the green hills pass us slowly by, a low hum reverberated from the rows ahead of me; the mother had begun praying and chanting, as she kneeled in front of her double-seated row, her elbows leaning on the seat at an angle, hands clasped together. A little later, she relocated to the row behind, adjacent to my seat and we struck up a conversation. Though she could not understand the content of my words, nor I hers, that mysterious force of communication that I had so often tapped into and revelled within, soon took ahold of our carriage. Mother and son were heading back to their home in Sighișoara. We spoke a little more and soon she began humming a folksy tune to her child. We parted ways at the station, but not before she abruptly cupped her hand to her breast, adopting a pose I’d sadly seen all too regularly in the past few days. Smiling, we drifted off down separate lanes.

The medieval town of Sighișoara and the more modern residential area are divided by the Târnava Mare river, at the edge of which sits the Holy Trinity Church opposite the old citadel on the hill of the adjacent bank. Given the prominence of unitarianism in the region, the name of the church seemed rather deliberately pointed as I wandered inside. Built in the early 20th century in a Neo-Byzantine architectural style, the gleaming exterior served as quite the contrast to the dim insides, following the Orthodox theme I’d first noted back in Târgu Mureș.

I left the church and crossed the river, entering the old fortress town from the north. Taking the cobblestoned path which wound up to the citadel, I soon passed through the Clock Tower, the symbol of the town and, as I would come to see, the ever-present character of the town — stretching out above the traditional rooftops keeping watch over the valley below. I had an oddly strong feeling of recognition when I passed through the archway below the clock face; I had been here before – during a family road trip when I was 11 – though this was the first time I had seemingly recognised something from that brief foray all those years ago! (On the subject of roofs, they adopted a similar style as The Eyes had in Sibiu: with dark and lichened hemispherical clay tiles, set into which were often open, unglazed windows.

Within the shadow of the old clock tower, firmly stationed in the citadel, lay an unassuming house (and now restaurant), which claims to be the birthplace of the most famous of all Romanians, he who goes by many names: Vlad Țepeș, Vlad the Impaler, Vlad the Dragon, Vlad Dracula. (The house has, however, been rebuilt since then.) Though born in Sighișoara, Vlad Țepeș was actually a Wallachian leader (the lands to the south, bordering Bulgaria and Transylvania), his continued erroneous connection with Transylvanian countship owes itself to Bram Stoker’s tinkering and the tourism industry thereon.

Down the lane a few more yards, I reached the central square, the Piața Cetății (Citadel Square). 16th Century buildings with clay-tiled roofs lined its sides and echoed the multicoloured palette of the old town as a whole. Just around the corner, I located my hostel, nestled in the very centre of the elfin citadel.

Thrilled by my arrival in this the epitome of an old Saxon town, I set down my pack and descended from the citadel to the Piața (square) Hermann Oberth in the old, external town below, where I sat in the square overlooking a small park in the centre.

And then the heavens opened.

I (quite literally) ran back up the hill to the citadel to my hostel, shed my pair of walking shorts for trousers, before descending again to find some food. Skipping up and down the cobbles as I went.

I found a burger place to get some supper before enjoying a beer in the square; the rain had abated by then. Prior to that, I did try to find an underground bar called Valhalla, but when I located a likely entry point down a sett-paved alley connecting the citadel to the downtown (complete with an inapposite Viking horned logo hovering above a wooden doorway), the door was locked. Around 11pm, I headed back to my hostel, of which I appeared to be the only resident of its 80 dormitory offering. This tiered old town really was the perfect little Transylvanian outpost, steeped in Saxon history: stereotyped and well-restored, but in the best of ways. That night, the rain returned.

School on the Hill

Journeying back to where I had caught the train the previous day, I soon arrived back in Sighișoara. On the edge of town, I came to a whitewashed building atopped by a bronze Star of David. The gate and door of the synagogue were locked and a group of old men were sat in the shade of the front porch smoking their afternoon cigarettes, no doubt hiding from their wives. A young woman across the street saw me trying the latch and helped me find the neighbour next door with the keys. A little old lady of some 60 odd years with a mop of black hair in a white summer’s dress appeared. All smiles, she introduced herself as Veronica and unlocked first the gate to the side garden and then the door to the synagogue. We rather effectively conversed using simple phrases of our respective vernaculars as she toured me around the relatively small site. Erected in 1903, the building had been restored in 2007 thanks to a Washington benefactor. The Jewish community is sadly no more in Sighișoara (as is the case in much of Romania and the countries through which I have walked) and the last service took place in 1984. It now serves as a part-time concert hall and historical building, with Veronica voluntarily maintaining the building and small garden. She was particularly proud of her topiary efforts; she had pruned a hedge into a star which surrounded a cherry blossom.

Returning up to the citadel, I ascended further, up the 178 steps of the covered Scholars’ Staircase (there is an old school up there too), to the aptly named Church on the Hill. I had summited the town. A clutch of tourists posed for photos between the cracks and arches of the old citadel walls. The Gothic church up top reinforces the Saxon origins of the town, and so too does the Saxon cemetery1 which trails off down the hillside, with graves almost exclusively bearing German inscriptions, just as much of the town’s signage had.

Charmed and taken, I extended my stay an extra night to recuperate and further explore: sipping flat whites in the lower areas of town, before later ascending to local dark beers up in the citadel.

That evening, I had been invited by a waitress I had met previously to a karaoke night at a locals’ pub. There I met a few of the graduating pupils of the (high) School on the Hill — a medieval remnant of Saxon (and German!) education in the centre of Romania. Soon, likely by my prompting, discussion round the table moved into the history of the town, whereon a couple of students relayed their Saxon or Magyar heritage. An inebriate newcomer joined the table, and steered the conversation to the Romani of town; predictably, his thoughts were hardly nuanced.

“Fuck Gypsies”, the skin-headed sage cried.

The conversation moved on, and so too did I.

Făgăraș

Two days later, having passed briefly through Sibiu county into Brașov county, I descended from the low-rise massif into Făgăraș. In the distance, across the plain, the snowy white peaks of the Făgăraș Mountains of the Southern Carpathians rose up: giants of rock far taller than those I had been crossing or passing these past few days. And somewhere to the south and slightly westwards, I espied the Moldoveanu Peak which, at 2,544 metres (8,346 ft), is the highest mountain peak in Romania. The acme was shrouded in the clouds, though its base and lower areas were visible below.

The town, exactly as my guidebook had forewarned, was ‘marred by communist town planning’. Decrepit concrete blocks of some five or six storeys made up most of the town. I sat having a shawarma – ordered in Spanish from an Italian-speaking Romanian – by the cathedral and then headed around the moat to the town’s castle, the only real sight of the place. By sheer fluke, entry was free as this happened to be the European Night of Museums. The castle exhibitions themselves were rather barren and lacking, though my observations were in no small part affected by my foul mood: when ducking out of a stone helix staircase, I had smacked my head on the wooden beam above the threshold. Hard. The redeeming elements comprised of the Stone Age and Dacian findings, and a room filled with medieval cartography of the region. Gingerly, I wandered in a daze around and up towards the throne room.

Built in a Renaissance style at the end of the 16th Century, the great throne room, on the second floor of the fortress, served as the centre of the Transylvanian Diet for many decades. More recently, the castle had functioned as a communist prison from 1948 to 1962, and the process of restoration following has remained incomplete, leaving an austere feel to a site with many stories to tell.

A long and happy day

When I set out the next morning, an Orthodox Sunday service was in progress in the cathedral. I passed through the crowds of people stood outside the entrance listening to the service from the bottom of the steps, where the loud chanting from within was being broadcast. I went inside. My attire immediately labeled me as the odd one out: not exactly garbed in my Sunday best, nor were my clothes remotely Transylvanian.

I walked along the road which followed parallel to the mountains to the south. A squad of bikers, complete with custom leather jackets, passed me by and later I walked by a roadside van filled with sacks of potatoes for sale. Soon, I turned south, into the early foothills of the mountains beyond, whose weighty presence I felt ever more as the day wore on. Outside the hamlet of Toderița, two peasant farmers called from the edge of the field over where they sat in the shade keeping watch over their flock of dark black cattle.

“Hora?” they called, pointing at their watch.

Consulting my digital phrasebook, I called back: “Doisprezece”. Midday.

The sound of hooves on gravel grew louder as I passed through the village, and soon a horse emerged pulling a family of eight all bunched into a small rickety wooden carriage. Behind, a foal followed, occasionally tapped on the rear by a stick wielded by the driver. Overtaken, I spotted a number plate, gleaming from the back of the old timber fame.

As I came ever closer to the foot of the mountains, the bosks, glades, and vales slowly fell away, leaving open expanses of fields on relatively flat terrain. I followed the path, which gradually mutated to a rockier dirt track through the fields. For a few hours, I was alone, barring a couple of cyclists no doubt headed for the mountains. With the trees around me having fallen away, the peaks solidified their prominence on the horizon. And now I could see the whole stretch of the Făgăraș Range: from where it rises from smaller mountains to the east, across to the upper climes of the snowy peaks, and through to the western ridges where it falls away into the horizon and fields. There was something idyllically charming observing the hypnotically snowy peaks whilst labouring in the sun’s rays on a hot summer’s day.

Water and religion in unexpected places

Bucium marked the closest I would come to the Făgăraș mountains. My various stores of water had been emptied by the time I reached the town, and my attempts to find a stream in the heat of the day had been unsuccessful. I asked a couple of locals where I could find water, however the rural store to which I was directed was closed. A couple of teenagers, maybe 17 years old, tried their best to help, but also to no avail. However, about 20 minutes later, as I walked east through the countryside once more, the young man reappeared on the road. Having added an extra member to his weekend band of young cyclists, across the now-tarmac road, he held out his water bottle! Quite the surprise. I took two long draughts and thanked him before he and his friends turned back towards Bucium. A true good Samaritan. His countenance and manner reminded me of my brother.

Later, to refill my own bottle, I asked two men outside a house in a hamlet called Șercăița. The old man, with a cheery complexion and a single front tooth, escorted me into the courtyard behind him, and bade me follow him into his chicken coup. There he ran a tap to cold and gestured me to fill my bottle. That I did, as tens of hens clucked and ran by my feet. I had often found in these small valley villages that there are an abundance of wooden benches, often retractable, in front of houses. Many look like they would crumble under the weight of even the smallest man. But they provided shady, if slightly unstable, resting points as I tracked by the mountains eastward.

As the afternoon sun passed its zenith, I spontaneously followed the sign for Sinca Veche cave monastery. Going in completely blind, I soon spotted a host of people slowly winding up the hill from the carpark in suits and dresses. Dressed in sports clothes and drenched in sweat, I overtook the crowd and entered this hillside garden. A whistle-stop tour ensued and I found myself in the middle of an old cave formation, and then scampering up to a small chapel at the top of the woods; the natural beauty subtly landscaped, its zen ambiance cleverly maintained.

It had been a very long and happy day in the sun by the mountains. The walking day ended as it had begun: with a walk down an A road. I was just starting to decline into a heat and hunger induced grumpiness, triggered by my finding out that the €8 motel to which I had been headed had no rooms left. I found, online, a different one slightly nearer (which further vexed me due to its higher price and its making tomorrow longer, though this was ultimately no bad thing as I needed to clean and rest).

However, the day was not yet done. As I huffed along the A road, a horse-drawn carriage drew up by me and, as the driver tried to steady his horse to a stop, he asked me where I was going and I gestured straight and shouted the name of my motel over the din of the surrounding traffic. The bronzed man tipped his straw hat and signalled for me to hop in. I threw my pack into the back and jumped in after it. On my very own Transylvanian horse-drawn carriage, we trotted the final couple of miles of the day through the woods and down the way.

- I learned later that evening that, in order to be buried in the cemetery on the hill, a requirement of Saxon heritage remained in place (as it had done since the early 17th Century). ↩

Wonderful! Loved every word. Glad for the interlude when your Dad joined you

for a spell. He must be so proud of you .. evidently sharing his love of

exploring different cultures .. and finding how alike we are. Maybe a book?

Thank you so much, Nelly! Your support means a lot. A book would be the dream 🙂 We shall see…

Well worth waiting for throughly enjoyed all your stories and wonderful photographs

Love Granny