On the steps of the palace

Leaving the minute village of Einsbach the next morning, I wandered around the countryside outside Munich and Dachau for a good few hours. I likely took the least direct route possible, looping around the grassy meadows, slowly zeroing in on the centre of Munich. But the weather was good, and I was approaching the heart of Bavaria: I didn’t care.

Having elected to bypass the camp at Dachau (I had been before, and I was in too high a spirit to consider a return that day), I made my way through the western suburbs of Munich. Stopping occasionally by parks, stations, and even a fishing lake, by the mid-afternoon I had reached my home for the next few nights: Schloss Nymphenburg — a wide, baroque palace, complete with landscaped gardens, just outside the centre of town, and once the summer residence for the rulers of Bavaria.

In the converted servant wing of the palace, I met up with Lilli (and later Charlotte) — two German girls around my age, who had very kindly agreed to host me. Both were currently on an FSJ (the German equivalent to a gap year, however considerably more structured – and I’d hazard even state directed – than our interpretation); they were working in the restoration department of the palace, hence their shared accommodation. This was my first taste of staying in the bounds of Europeans aristocracy: Paddy would be proud. Upon my arrival, I discovered that Charlotte would not be back till late, as she was taking her voluntary youth group out climbing (Klettern) in town. That evening, I hung out with Lilli and her friend Maggie, who was also on a gap year, and had recently returned from an intense English course in Boston, followed by a solo driving tour across Germany, specifically university towns — we had a long discussion about our experiences in Heidelberg and Mainz: yes, I had found my people.

Lilli and Maggie had prepared a supper of fried vegetables and Pommes; I must admit I felt rather embarrassed when, a few minutes after my arrival, I emerged from my room, all changed from my “road” gear and coated in a fresh blanket of deodorant, and pronounced “right, how can I help!?”, only for them to announce that everything was prepared. Laughing in self-deprecation, we sat at the kitchen table and began discussions that lasted long into the night.

After supping, we played a whole host of different card games: they taught me Arschloch and the German iteration of ‘Wizard’, and I, being the sophisticated cards player that I am, taught them ‘Cheat’. And mostly, we talked. Lilli and Charlotte both worked in the palace and sometimes travelled to other Bavarian stately homes to help out. Lilli wants to do a degree in restoration, and I later discovered that Charlotte wishes to become a carpenter. (Whilst I have enjoyed my travels no end, I would like to take this moment to clarify that a nomadic profession is not my end goal here. Though I guess that remains to be seen.)

Lilli was heading back home to her village in the very centre of the country in the early hours the next morning. Her family owns a farm which, during the summer months, employs Ukrainian workers; her brother had headed off to Ukraine via Poland to pick them up and transport them and their families to Germany for refuge. And so she was going home to help look after the families and the Ukrainian children for a while. It was heartening: she spoke of them so fondly.

After Maggie departed and Lilli went off to pack, Charlotte arrived home; we spoke for a bit before exhaustion overcame me, and I retired to my quarters. My room was the third bedroom of their palatial apartment — their 30-something year-old ex-roommate, a gardener, had just moved out. The room was enormous, with broad, ligneous floorboards and mullioned windows which overlooked the cobbled courtyard below: the biggest room of my trip thus far. Within the palace walls, I fell into a heavy slumber.

Beerhalls, gardens, and churches

I woke up late and well-rested the next morning, and spent a little while figuring out the best public transport solution for my days in Munich. Catching the metro from Laim, a 15-minute walk from where I was staying, I headed into the centre of town. Marienplatz – the main square and de facto centre of Munich – was my destination. A few blocks away, in a garden square, I sketched out a list of sights to see over the coming days.

My first port of call was the Rathaus’ courtyard, followed by the Frauenkirche, then Peterskirche, and then Heiliggeistkirche; a plethora of churches make up the old town of Munich. I closed in on the twin, green domes of the Frauenkirche, which poked out above the rooftops of town. Initially, the interiors of the church struck me as rather bare compared to the great Gothic cathedrals I had come across further north; however, the brighter, white style grew on me. It was decidedly Bavarian — there was something pure about the cleanliness and airiness of the place.

After a Weißwurst from a street vendor, my first grub of the day, I found a Brauhaus in which to sit and write and, more importantly, sample some Munich beers; two Dunkelbiers later, I made my way to the Hofbräuhaus. Rinse and repeat.

First thing the following day, I headed to the gardens of the Schloss next door to check that my stick was all safe and sound where I’d stashed it two nights ago: all was in order! I caught a tram into the centre and alighted at Sendlinger Tor which is situated right at the bottom of the old town. Walking north through the Altstadt, passing the haunts of yesterday, I popped into the Asamskirche: a baroque chapel and set into the street line. After looking around the courtyards of the Residenz, I then wandered around Maxvorstadt, where the university is based. I ate my burrito lunch in the sun, sat on the steps of the History and Architecture department.

The rest of the day was spent in Munich’s Englischer Garten (English Gardens); a sprawling landscaped park in the centre of town which rivals even Hyde and Central parks in both size and stature. Paths meander through grassy meadows and river banks, through curated forestry, and follow the banks of lakes further north. By the Chinese water tower, even at the backend of winter, the biergarten sat exposed in the sun at near-full capacity. It was glorious, busy, and calming.

That evening, we headed back into Maxvorstadt to meet up with some of Charlotte’s friends and play a few rounds of pool. (For some reason, they seemed to refer to ‘pool’ as ‘billiards’, which was rather confusing and, apparently for me, a noteworthy oddity: inevitably sending me down a 1am Wikipedia rabbit-hole later that evening. When we drew up back at the Schloss in the early hours, I vacated the spare room to make way for Charlotte’s friend from home (around Lake Constance) who had just arrived. Beding down for the night on the floor in the kitchen, I soon fell asleep, the floorboards of the quarters creaking wearily, responding to any subtle movement on my part.

Approaching Austria

Shortly after my early rise the following morning morning, I set off. Heading out of the castle wing I’d been staying in, I thanked Charlotte, who bade me farewell, as she headed out towards the restoration workshops across the courtyard. My first port of call should come as no surprise: I walked purposefully to a particular spot in the public gardens of the Schloss and retrieved my stick from its temporary hiding place, a bush behind a fence, no doubt providing puzzled amusement for onlookers. I then took a metro train which deposited me on the other side of the old town, using up the last of my Munich metro credits. And from there, I walked out of the city.

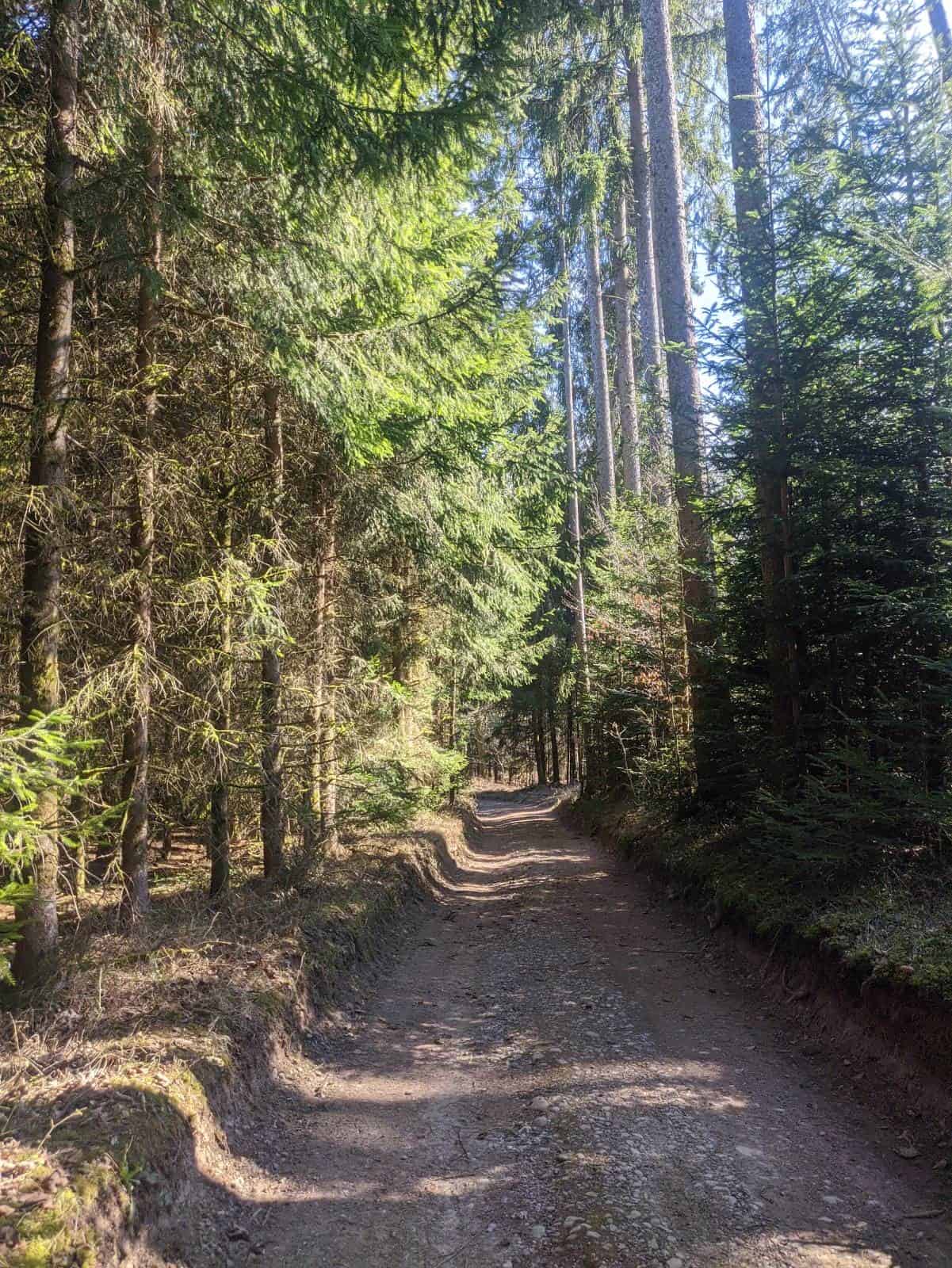

After a few hours, I left the rather repetitive outskirts of the city’s suburbs and reached a great forest of green. I walked a meandering path through the Eglhartinger forest for a couple of hours. Stopping occasionally to read, I took my time ambling up and down the gentle banks in the sun-dappled undergrowth.

I arrived in Ebersberg around 4pm. Reaching my inn in the centre of town, I immediately got to work putting together a makeshift sandwich picnic out of Lidl supplies and sat in the sun by the rococo Pilgrimage Church, taking in the Bavarian sun. By now, it was beginning to dawn on me: I only had three nights after this left in Germany. I was making progress, but also, moving on. It was all a wee bit confusing — at least for a short while.

The inn I had procured was in the centre of town, and was attached to a brauhaus. In an unmistakably Bavarian style, the interiors consisted largely of light-wooded panelling, with pastel paints and faintly wallpapered faux-millefleurs covering the areas in between. It was what was hanging on the walls at regular intervals – or perhaps more accurately, what had been slotted into the walls – that most bewitched me; miniature portraits of Bavarian-styled figures filled the hallways of the inn: Landsknecht soldiers, aristocracy, and peasants clad in lederhosen and dirndl. A vast variety of characters had each been individually painted onto the wall panels: the flickering lamps of the hallways, animating them — as if in arrhythmic motion. An inadvertent chronophotographic effect. The walls were alive; one could almost hear the mediaeval hubbub echoing through the halls and picture the scenes of merrymaking.

Rural Bayern

The roads that I followed during the final few days in Germany had a distinct character about them; those hours of walking were unmistakably Bavarian in their bucolic nature. The roads wound around the hills and sleepy villages in an almost languid manner. The Kalkalps (Limestone Alps) stayed by my side, always looming in my periphery, seeming to grow day by day, as I walked eastward. Distributed in fields along the roads at varying intervals, sat shrines, often parked next to benches. These crucifixes and Virgins were a constant reminder of Catholicism’s dominance in the south of the country; they highlighted the divide in Germany between the Protestant north and the Catholic south, a divide still apparent today, yet perhaps not felt quite as starkly as it once was. What had been harked upon to no end in the German and History classrooms of school was palpable in the field(s). The proud shrines erected by farmers played nicely with the pilgrim image as I passed: I liked it.

It was on this last Bavarian stretch, perhaps inspired by the rolling Germanic hills I followed, or by my reminiscences of the past month or so, that I began to commit fragments of German poetry to memory; in rather erratic fashion, as I walked the Bavarian leg, I read and recited back fractions of German romantic verse. The narrow, dusty lanes down the side of busy roads hardly serving as the ideal dramatic classroom, only a couple of verses of Goethe’s Erlkönig and the odd line of verse from Heine’s Lyrisches Intermezzo (the inspiration for Schumann’s renowned song cycle Dichterliebe) lodged themselves securely in my mind; a topical (though not exactly superficially uplifting) addition to my evermore idiosyncratic repertoire for the road; I made a mental note to return to the wider corpuses when the climate was more accommodating.

’Even to the frozen ridges of the Alps…’

Just west of a town called Pfaffing, I brought up 500 miles for the trip; I marked the occasion with a suitably Gen Z TikTok-style video set to the song “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)” — an apt idea of my brother the night before.

Not long later, I spotted the Alps for the first time. They appeared rather suddenly, just as I reached the brow of a hill. Sitting on the haze of the horizon, their snowy peaks a chalky smudge streaking across the welkin.

Set on a promontory, on a sharp bend in the river Inn, sits the town of Wasserberg, where I arrived that afternoon. The small town was filled with little arcades and covered walkways with low Gothic arches lining cobbled lanes. The buildings of the old town had been painted a range of pastel colours. From a café in the middle of town, I sat and watched the distant rugby, sitting at one of a handful of tables which spilt out into the square.

Having departed Wasserburg the next morning, I ascended the hill on the other side of the river Inn to take in the town. The knell of church bells rang out through the countryside as I walked. It was Sunday: my last day of rest in Germany — securing supplies would again be an issue. Though, the scenery was breathtaking; the Alps were becoming ever more consolidated on the horizon. It was a long day traipsing through the hills and forests of the Bavarian countryside. The subtle chill of the last few days had abated, leaving the same clear blue skies and unobstructed sun behind: it was getting hot.

In the late afternoon, a mirage of water come into frame, and so too did the twin green peaks of the monastery I had been tracking – or more aptly, that I had been circuitously ambling across the hinterlands – towards: Seeon Monastery. Wandering through the various chapels, having refuelled at the resident café on sausage and honey mustard, I ended up at the back of a small service in a side chamber.

Back on the road once more, I was fast approaching the freshwater lake of Chiemsee, a popular summer holiday destination. Hues of purple, yellow, pink, and red took to the skies as I approached the lake, heading south towards and the Alps. The colours formed a gradient down the sky, with the mountains looming ever larger on the canvas. An increasingly dark blue tone grew gradually stronger, eventually blanketing the fullness of the sky; though, for a short while, the last embers of those other vibrant hues flickered in that crevice above the horizon. Soon, blue turned black. And with clear night skies – the stars above and the Alps ahead – I headed to bed in the lakeside town of Seebruck.

The following night, in a small village not far from the Autobahn called Neukirchen am Teisenberg, I found the only Gasthof in town and settled down for my last night in Germany. It was in many ways the ideal final night in Germany: a tiny village in the middle of the Bavarian countryside, with its own a small, white church, Gasthaus, and a view up into the peaks of the Alps. This was the closest I’d got to the foot of the mountain range; I was almost within touching distance. The Gasthof doubled as the only restaurant in the town; it was so stereotypically Bavarian, but with a palpably folksy and authentic feel — far removed from the Epcot experience. Having sat a while outside the village church admiring the mountains, I went back into the Gasthof, ready for the evening. I was seated in a timbered and homely dining room, which got busier and busier as the evening went on, as the rest of the village gradually stopped by. Scrutinising my menu, I stifled a laugh when I realised that all the nonalcoholic beverages were notably more expensive than their inebriate counterparts: when in Rome. I asked the waitress, who was suitably clad in Tracht, which dish she would recommend given my hunger. She laughed and replied enthusiastically: whatever I ordered, the plate would be piled high. She was right.

Exodus

My time through Germany was rapidly reaching its conclusion. The stretch between Munich and the Austrian border felt rich in Bavarian culture and landscape, but had a genuine feeling of dénouement about it. (Strange in a way, given I still had a whole Germanic country to cross yet; though, perhaps that’s what comes with the excitement of walking across an entire country for the first time?) My practice through most of Bavaria had involved walking up and down hilly dirt tracks, through farms and countryside, walking through faint paths in the woods, or heading along the side of winding B roads, dodging the odd car and waving at passersby, calling out “Servus!”.

The past 46 days I’d spent walking across Germany had been varied, beautiful, difficult, and rewarding. The journey had been fuelled through the permanent fixtures that were German discount supermarkets (Lidl, Aldi, Penny, Netto, REWE, etc.), bakeries on every corner of even the most obscure town, döner kababs ranging drastically in quality, and quality, local beers. But most significantly for me, it was travelling through Germany where I realised that what I was doing, what I wanted to achieve, was possible: I could work within my budget, I could visit new places, meet new people, experience different cultures, and speak other languages. All this and more, whilst travelling on foot. I learnt a lot in Germany — about myself and about the function of my trip. I learnt that I could cope by myself in foreign worlds and situations, but most importantly, I learnt that I could make this work: I could walk from here to Istanbul. It was feasible, and I was unreservedly invested.

Following a single carriageway through the Bavarian hinterlands to the border, ducking expertly out of the way whenever a car came down the road, I arrived in Ainring: my final German town. There, I stopped quite ceremoniously at a bakery in town and picked up some early lunch. (The server complemented my German accent, which felt most appropriate given the location’s significance.) A mile or so east of town, I crossed the river Saalbach into Austria. And left Bavaria and Germany behind me just as I had entered — on foot.

The logbook has updated. Click here to view.

Loving your journey!

Wonderful Noah I felt I was with you A most enjoyable read

Granny xxxxx

A most descriptive story of your daily travels Noah and informative and interesting photos.

Granny & I look forward to reading your next Chapter through Austria where A Lilli was born & grew up (Graz) and where my father did his walking and climbing in r

The Alps in the 1930’s, after leaving the Black Forest area!

Hope to speak to you later today

Take care & enjoy Grandpops!

Hullo Noah, I have just joined you in Slovakia ……. this is wonderful stuff with brilliant photos … keep posting, I will be with you all the way to the shores of the Bosporus.

Many thanks, Jane!